The Last Outpost

A collection of articles and thoughts by Dr Chris Ellis

Saturday, October 02, 2004

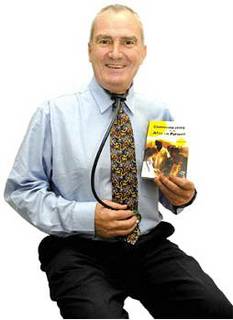

Getting the story right by Janet van Eeden

I heard of a misunderstanding in English the other day when the patient complained of snoring and the doctor thought he complained of a sore ring and gave him ointment for his piles," says general practitioner Dr Chris Ellis. "I don't know whether the patient put the ointment up his nose or not."

This story is just one example of how communicating across different cultures can lead to serious misunderstandings. Language barriers are just one of the obstacles to overcome in treating patients with different backgrounds to the presiding doctor, but cultural barriers are sometimes even more obstructive. Hence the book that Ellis has just written. He has facilitated workshops on cross-cultural communication since 1999 and found a great need to explore the topic further to clarify issues that have been problematic. And so the book, Communicating with the African Patient, was born.

I asked Ellis about the title. In our days of extreme political correctness, the title does appear to be patronising. Ellis explains that he and his publisher "did struggle over the title. The title is Eurocentric, I think, and obviously addressed to Western doctors and nurses. Although it could be interpreted from a South African view as possibly condescending, it is not meant to be so," Ellis explains. "I don't think it would be considered patronising from an overseas perspective. The message of the book is to establish clear communication between cultures, in the sense of receiving and giving messages to each other that are not misunderstood. However, I do agree it could go both ways. It could be entitled 'Trying to Understand the Western Doctor'. Perhaps that should be my next book!"

In fact, the subject matter of the book addresses very real issues of confusion, which arise specifically from the different perspectives of the Western doctor and the traditional rural African patient. Ellis treats the matter respectfully and without making value judgments about which world view is correct. As such, the book makes an interesting read, even for those not involved in the medical profession.

Ellis writes at one point about treating an elderly weaver whose rhythms of life are in tune with nature. Time is judged according to the 13 moons of Zulu culture. When the man is ill, he has to go into the Western clinic, a place as terrifying and foreign to him as a strange land. His illness also has to be explained as separate from his mind - a concept not usual to him where "his dreams, his feelings, his telepathy and his visions are part of his tangible body". Add to this that he is constantly in communication with his ancestors. Once the challenge of diagnosis has been met, the Western doctor has to explain to this man of nature how to treat his body in purely scientific Western terms.

Ellis explains that "one has to assess the patient's belief system, which - like all of us - is an eclectic mixture of the individual's, family's and also the community's health beliefs". As such, the need for time and understanding is emphasised. "Research has shown that most doctors interrupt their patients after only 18 seconds of listening to them. This same research has also shown that it takes the patient only a minute-and-a-half to tell his or her story. Carl Jung once commented that 'A diagnosis helps the doctor but for the patient, the crucial thing is the story.' Jung was right. Every patient has a story. Every community has its story. And in the telling of the story, the patient communicates anxieties and perceptions. The story becomes a metaphor for their lives. If the doctor isn't able to take the time to listen to a patient, he will miss being receptive to the cue and clues given out by the patient in distress."

Ellis stresses the importance of understanding the particular patient's story at any one time. If the doctor isn't trained in the language or the idiom of the language of the patient, then much will be missed. If you add an interpreter to the mix, the patient can be cut out of the communication process both literally and figuratively, Ellis explains.

"When you think that only seven percent of meaning is conveyed by words alone, and 55% by non-verbal body language and facial movements, we realise how important it is to understand where your patient is coming from," says Ellis. "The remaining 38% is conveyed by the tone of the voice and its fluctuations. All these aspects have to be taken into account in communication, especially when the balance of power in the doctor/patient encounter is more than usually uneven. For example, I, as a white older male doctor in a white coat, encounter a young rural Zulu girl in consultation. She feels that the doctor holds all the power, as an older male who is traditionally accorded much respect. Add to this my white coat, which is symbol of my education, and the fact that I may drive an expensive car. The power differential in that is enormous. One would have to be careful not to misinterpret her reticence for anything other than respect at first."

Ellis also speaks more about the different world views of patients. In traditional African beliefs, the mind and body are indivisible. How does this apply to the duality of depression and illness? More and more it has become apparent to experts that there is very little division between sickness of the mind and sickness of the body. I asked Ellis which comes first - illness or depression? He answers that it is very much a chicken and egg situation as every illness carries with it symptoms of anxiety. "In certain cultures, certain things are more sociably acceptable than others," he explains. "So sometimes a Western technologically culture-bound person finds it more acceptable to have a suspected brain tumour than to have depression. And just so, a person with a traditional African world view will be able to explain the disease by saying that the ancestors are angry or that a spirit has possessed him or her, for example."

I wonder if it is ever possible to get to the bottom of illnesses at all with the quagmire of miscommunication that seems to exist between people. Ellis is reassuring. "The patient usually goes to the doctor in his role as a body mechanic to get parts fixed. Usually there is a simple problem that is easily solved by application of a prescribed medicine. These are the easy cases."

But for the more complex problems Ellis states that it is difficult in the rush of modern life to listen to the patients as "the time in a hospital outpatients' clinic is so short and the patients so many. Possibly this is why patients go to the traditional healer or priest to restore the equilibrium in their lives."

Regarding the traditional healers, Ellis says there is a place for everyone in this world. As long as everyone involved adheres to a few solid Latin rules. The patients have to take into account "Caveat emptor - Let the buyer beware." And the healers have to follow the ethical code of doctors, which is "Prima non nocere - First do no harm." Sounds like a positive message for healthcare, in all its guises.

Publish Date: 1 October 2004